January 20, 2026

Exposure, frequently described as the “crown jewel” of behavioral therapy (ten Broeke & Rijkeboer, 2017), is often considered the preferred intervention for a variety of anxiety symptoms and disorders (Hofmann & Smits, 2008; Norton & Price, 2007). When we think about exposure therapy, we typically think about fear of spiders or social situations, yet sometimes the fear can be far more internal. ‘Laura’, a woman in her early thirties, wasn’t afraid of crowded places or heights, but of her own body. She avoided coffee, exercise, and even climbing stairs because any change in her body could “trigger” a panic attack, and she was eventually diagnosed with panic disorder. In this article, I will explore how exposure therapy can be applied in practice by sharing Laura’s story.

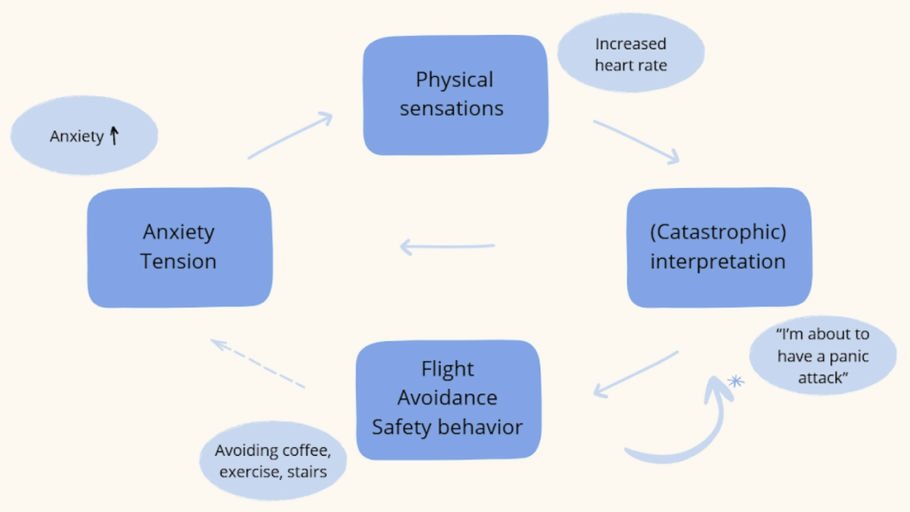

Our behavior is mostly guided by the short-term consequences it brings (and yes, avoiding something - not doing something - is also behavior) (Raes, 2020). When Laura, for example, is about to exercise, she feels a wave of uncomfortable tension. She quickly decides not to work out, which makes the tension disappear and leaves her feeling instantly better. This sudden drop in tension (and/or anxiety) validates her belief that exercising must have been negative or ‘unsafe’. “See? I skipped the workout, the tension suddenly disappeared and I felt a wave of relief, so exercising must be scary” (Raes, 2020).

Without realizing it, this positive outcome of avoiding (that is, the drop in tension as well as the relief she experiences) makes Laura more likely to ‘choose’ avoidance again in the future (Raes, 2020). Over time, the likelihood that she will exercise again decreases. By avoiding, she misses the opportunity to discover that exercise may not be as frightening as she thinks, and might even be fun. Avoidance keeps anxiety and other unpleasant feelings present, and often makes them grow (Raes, 2020).

In the short-term, avoidance takes away positive outcomes, and in the long run it can leave you stuck in fear, and maybe even sadness and self-anger (Raes, 2020).

Previous research indicates that exposure is an effective intervention for anxiety symptoms, with immediate success rates of approximately 50% and long-term rates around 55%, for children (Hofmann et al., 2012) as well as adults (Carpenter et al., 2018; Hofmann et al., 2012; Springer et al., 2018). Specifically, a number of studies have shown the positive effect of interoceptive exposure for a panic disorder (Arntz, 2002; Craske et al., 1997).

During interoceptive exposure, patients are exposed to physical sensations, to learn that these are not indicators of an impending catastrophe, like a heart attack or a stroke (Van Emmerik & Greeven, 2020). This type of exposure was introduced in therapy to help Laura confront her fear of bodily sensations. It is important to note that both the approach and its effects can differ from patient to patient and from symptom to symptom.

This article serves as an example of how exposure can be applied and what effect it may have on someone struggling with anxiety, however, it should not be seen as a one-size-fits-all approach.

At the start of therapy, Laura felt stuck with her bodily sensations and discouraged, believing she had “already tried everything”. When her therapist first introduced exposure, Laura became very anxious, fearing she might lose control. At the same time, Laura experienced a sense of reassurance when she learned that the process would be taken step by step and that she could pause at any time. It was also valuable to share several successful cases from the clinic, highlighting the value of motivating clients throughout therapy.

Before starting the exercises, Laura’s therapist took time to provide psychoeducation about anxiety (Hermans et al., 2017). He explained how anxiety manifests in thoughts, physical sensations, and behavior. The therapist described anxiety as our natural survival system, which is designed to protect us from danger. When we encounter a dangerous situation, anxiety alerts us and prepares the body for action through the fight-or-flight response.

For example, when crossing the street and suddenly seeing a car speeding towards you, fear-related physical sensations such as a racing heart help prepare you to react quickly and escape the unsafe situation (Barlow et al., 2017). In this way, anxiety serves an adaptive and protective function. However, the therapist emphasized that Laura’s survival system has become overactive, like an alarm that is set too sensitive, which causes her body to often give false alarms when there is no real danger (Hermans et al., 2017).

Understanding the role of anxiety and how the alarm system can become hypersensitive, set the stage for the next step: interoceptive exposure. Interoceptive exposure consists of two phases (Van Emmerik & Greeven, 2020). The process starts with exercises designed to simulate panic in the safe, controlled environment of the therapy room. Later, the exercises move into everyday life; the exposure is still planned, but the broader setting, such as the presence of others, makes (re)actions less predictable (Van Emmerik & Greeven, 2020).

The therapist emphasized that the goal is not for Laura to never experience a panic attack again, but rather to reduce her anxiety and avoidant behavior (Scheveneels, 2024).

Following this explanation, Laura’s therapist clarified that the exercises were intended to provoke physical sensations, especially those linked to distressing expectations about what the sensations might do to her, and which significantly limit her in her day-to-day life (Van Emmerik & Greeven, 2020). Laura was instructed to focus her attention both on this specific physical sensation and on the outcome she feared most. After each exercise, she was asked to what extent her expectation about the damaging effect came true. In this way, she could learn that while these physical sensations may be uncomfortable, they are not dangerous (Van Emmerik & Greeven, 2020).

The first exercise Laura’s therapist introduced is called overbreathing, also known as the hyperventilation provocation (Van Emmerik & Greeven, 2020). Before starting, Laura was given an explanation about hyperventilation. The therapist also noted that while the sensations might feel uncomfortable, they are harmless; the ‘issue’ lies in the catastrophic thoughts rather than the physical sensations.

For this exercise, it is important to introduce it as early as possible and to repeat it at the beginning of each session, as long as it evokes catastrophic thoughts; and especially in Laura’s everyday life beyond the therapy setting. The hyperventilation provocation should last for at least one minute and be prolonged if necessary until the patient experiences interoceptive sensations (Van Emmerik & Greeven, 2020). During the exercise, Laura experienced tingling and mild derealization, similar to what she felt during her panic attacks. During one of the hyperventilation trials, her therapist noticed a clear shift in her anxious interpretations of the sensations: Laura indicated that the sensations felt like the beginning of a panic attack, yet once she reminded herself they were not dangerous and allowed herself to experience them, she realized she was actually fine.

The second exercise Laura and her therapist tried was running in place. Laura was asked to run as fast as she could, without moving forward, while lifting her knees as high as possible (Van Emmerik & Greeven, 2020). The exercise should last between 90 seconds and two minutes, and typically provokes a faster heartbeat and noticeable shortness of breath (Van Emmerik & Greeven, 2020). When trying the exercise, Laura experienced a strong heartbeat and a sensation of body heat.

The third exercise Laura and her therapist practiced was spinning gently for one minute. For this exercise, they stood facing each other, with two chairs placed beside them. The therapist explained that he would begin spinning at a pace of one turn every three seconds. Laura was then asked to spin together with the therapist, keeping the same tempo. This exercise typically provokes dizziness and nausea (Van Emmerik & Greeven, 2020). Laura experienced light dizziness and a sharp rise in anxiety.

After interoceptive exposure in therapy, the next step is naturalistic interoceptive exposure (Van Emmerik & Greeven, 2020). Instead of practicing in the controlled setting of the therapy room or at home, patients deliberately engage in everyday activities that trigger physical sensations and test catastrophic thoughts. The key difference is that these exercises take place in real-life situations, with unpredictable (re)actions from others (Van Emmerik & Greeven, 2020). Laura slowly resumed everyday activities, such as climbing stairs on her own, taking the metro during peak hours, and returning to the gym for short treadmill and elliptical sessions. This process of naturalistic interoceptive exposure required time, with some activities being more difficult to return to than others.

Through the exposure therapy, Laura noticed something crucial: the physical sensations were uncomfortable, but not dangerous. Contrary to what she had always believed, nothing bad happened while experiencing these changes in her body. With practice and effort, her fear began to drop. Slowly, Laura returned to exercise, first just a few minutes, then longer sessions. Her heart still raced, but now she recognized it as a normal bodily response rather than a warning sign.

Most importantly, the process of exposure helped her stop treating her own body as a threat. Laura’s story shows that (interoceptive) exposure does not simply ‘erase’ all difficulties and anxiety; rather, it can mark a significant breakthrough in the cycle of avoidance and can support the regaining of a sense of control over life. It should nevertheless be emphasized that this article offers only a concise overview of Laura’s exposure process, with certain steps simplified for readability. In practice, such a process requires time, often including a range of obstacles and adjustments along the way. Finally, while certain exercises may be practiced independently, the guidance of a qualified health professional can provide essential support and help ensure the process remains safe.

If you're interested in the sources used for this article, contact us.

Footnotes:

Stay up to date on our work, our awareness raising and advocacy efforts, our latest publications and of course, all our (sports) events by giving us a follow on social media or subscribing to our newsletter.

Stay up to date on our work, our awareness raising and advocacy efforts, our latest publications and of course, all our (sports) events by giving us a follow on social media or subscribing to our newsletter.

January 20, 2026

November 25, 2025

November 13, 2025

October 18, 2025

October 6, 2025

September 19, 2025